NYC 25x25: A CHALLENGE TO NEW YORK CITY’S LEADERS TO GIVE STREETS BACK TO PEOPLE

Taken together, streets and sidewalks are New York City’s largest publicly owned space. Cars dominate that space. Despite the spatial abundance of 6,300 miles of asphalt and three million free parking spaces, New Yorkers’ everyday lives are relegated to narrow sidewalks and the margins of streets, where we are left to fight over the precious remaining scraps of our public space.

In the past two decades, elected officials have made little citywide progress in upending this wholesale car dominance — opting for disconnected and piecemeal improvements that fail to effectively manage our streets as a system of public spaces. For New Yorkers, the negative effects of a car-filled city remain. Asthma, heart disease, and preterm births rise with car pollution. Carbon emissions remain high and climate change threatens our future. New Yorkers risk life-altering injury and death crossing the street. Bus riders waste time on gridlocked streets. Burdensome commutes and a lack of transportation choices isolate communities from opportunity.

With a coalition of more than 80 unions, and economic, educational, environmental, disability rights, and public health organizations, Transportation Alternatives challenges New York City’s leaders to end this vicious cycle by making a specific and substantial promise: to convert 25 percent of car space into space for people by 2025.

Today, New York City faces a budget shortfall, a crisis of racial injustice, rising inequality and traffic violence, the loss of millions of jobs and small businesses, and the ongoing threat of climate change. Our recovery can begin, in part, by reimagining our largest public asset — New York City’s 6,300 miles of streets and three million free parking spaces — in support of the needs of all New Yorkers.

Source: Scott Heins / TA

Source: Scott Heins / TA

AN INEQUITABLE ALLOCATION

Streets are the single largest public asset in the City of New York — more than 6,300 miles of roadway crisscrossing at more than 39,000 intersections covering more than 120,000 city blocks. The lives of 8.6 million New Yorkers largely play out on the slim sidewalks that edge this massive network — the vast majority of everyday human activity relegated to the margins.

Today, though a minority of residents drive a car to work and a supermajority walks, takes public transit, or rides a bike, most of New York City’s streets are designed for a car-driving minority. An overwhelming 96 percent of New Yorkers walk to and from public transit, but public space devoted to the movement and storage of cars includes some 19,000 lane miles for driving and three million free on-street parking spaces — more than 1.5 spaces for every registered vehicle in the city — accounts for more than 75 percent of our shared streetscape. The remaining scraps of space are devoted to car-free bus lanes (0.02 percent), bike lanes (0.93 percent), and sidewalks (24 percent).

People who live outside New York City drive 4.4 million cars and trucks through city neighborhoods every day. Traffic-clogged and dangerous streets cost the City of New York and its residents more than $6 billion a year in traffic crashes and lost time. Low-income communities and communities of color bear the burden — longer commutes, hotter neighborhoods, worse air pollution, higher asthma rates, more health conditions related to car pollution, and more premature deaths.

A better future will require a new management approach from city officials — one that sees streets as a system of public spaces designed to serve people and breaks from traditional thinking centered on moving and storing cars.

Source: Andrew Hinderaker

Source: Andrew Hinderaker

By converting a sizable and significant portion of car space into space for people, New York City’s leaders could be the first generation to address to inequitable distribution of space that has harmed New Yorkers for generations.

Now is the time to take bold steps to correct a fundamental imbalance in our public space and who it serves — and give New Yorkers back our public space.

THE PROMISE OF FEWER CARS AND MORE SPACE

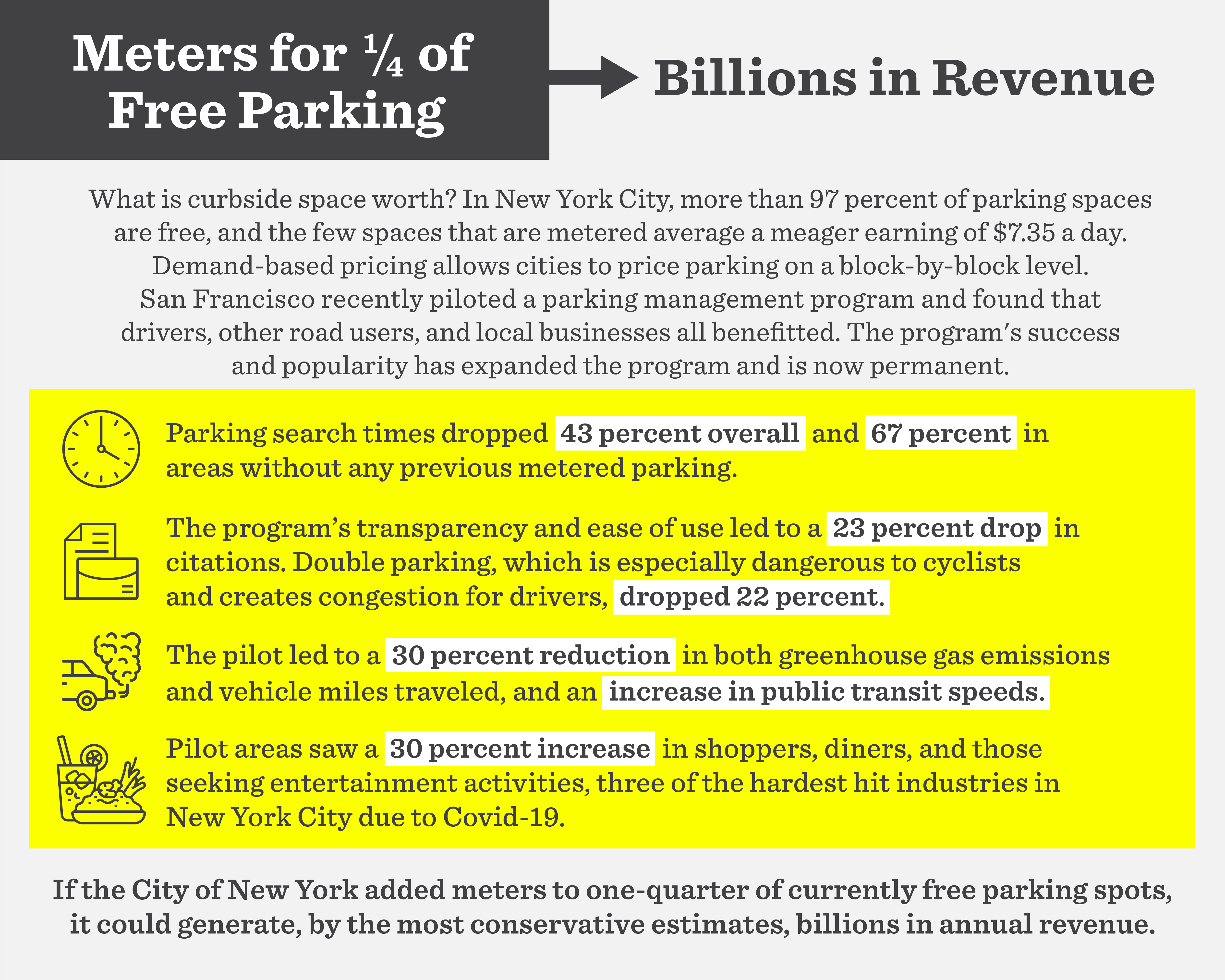

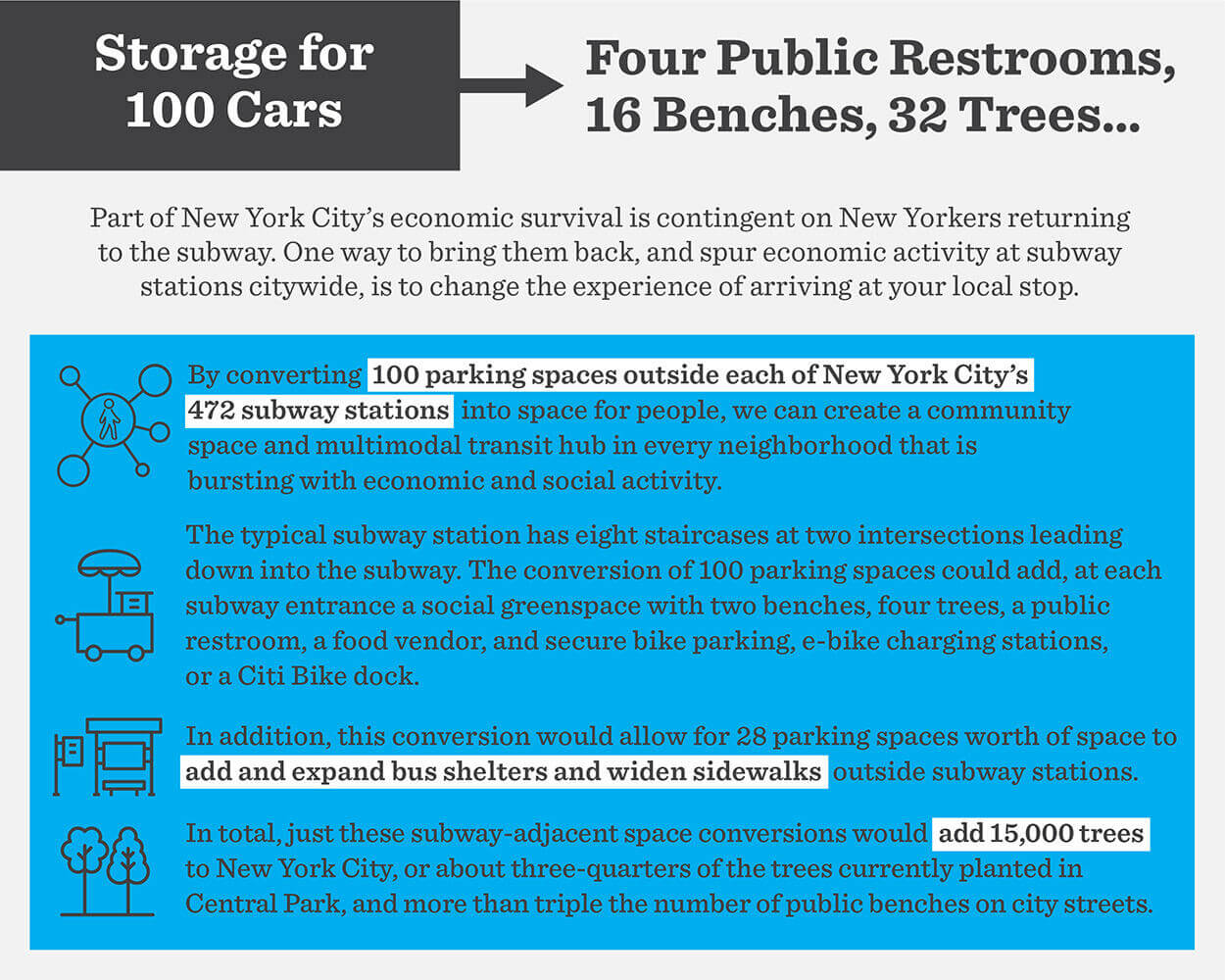

Following the public health and economic crises of 2020 and 2021, and the budget crisis facing the City of New York, and with congestion pricing and its predicted massive drop in car traffic to central Manhattan on the horizon, addressing these inequities is timely. It is also smart. Converting car space into expedited bus routes, safe bike routes, and expansive space for neighborhood life is both highly popular with New York City voters and proven to create more jobs and bring significant economic benefit for small businesses and city budgets alike.

Changing our streets starts with setting our priorities. If our streets are public space, then what is the best use of that space? Is it storing a few cars for free, or making space outside a local school for storytime? Is it prioritizing one commuter in a private car or 50 commuters on a public bus? Is it widening streets for oversized SUVs, or widening sidewalks so people with disabilities, older New Yorkers, and children can move about without fear? Is it double and triple parking, or planting trees to reduce pollution-induced asthma?

City streets are rich with the potential to serve the public good and improve the lives of all New Yorkers — if only that space were not devoted to the movement and storage of cars owned by a minority of New Yorkers.

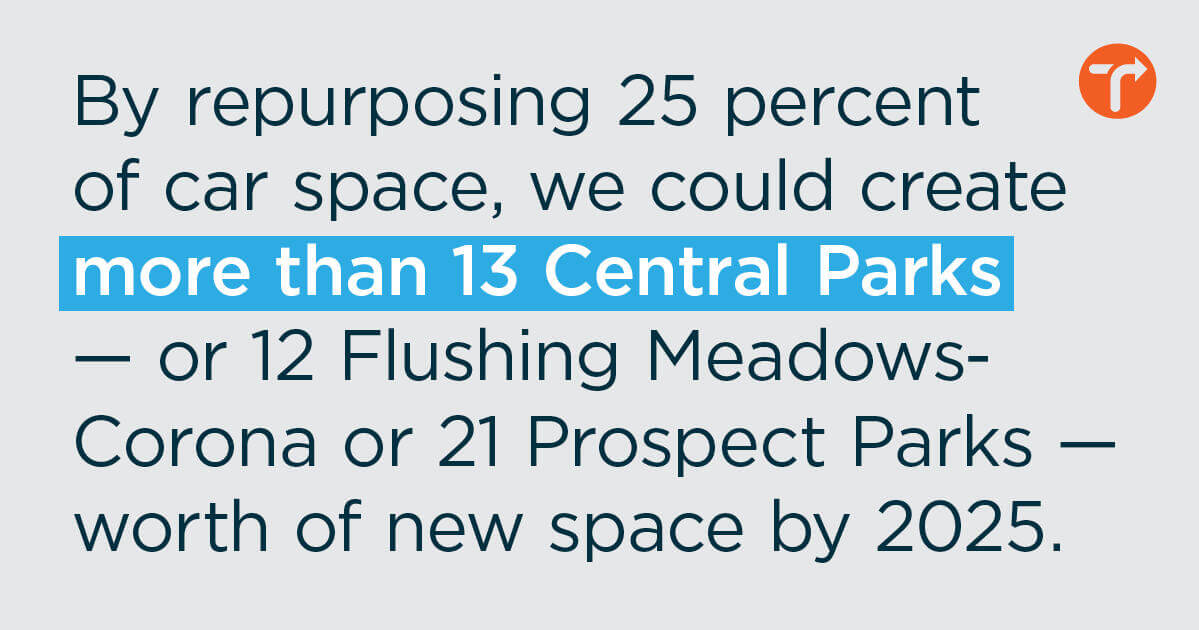

By repurposing 25 percent of current driving and parking space, the future leaders of New York City could create more than 13 Central Parks — or 12 Flushing Meadows-Corona Parks or 21 Prospect Parks or six Staten Island Greenbelts or 11 Van Cortlandt Parks — worth of new space by 2025. With that space, the leaders of New York City could:

- Expand Transportation Options and Park Access. Ensure that every New Yorker lives within a five-minute walk of a car-free protected bus lane, and within a quarter-mile of a protected bike lane, and within a five-minute walk of public green space, and within a block of a bike parking space, and within the access area of a newly citywide Citi Bike bike share system.

- Give Power Over Public Space Back to Communities. Allow communities across New York City to decide the best possible alternatives for streets in their neighborhoods.

- Spur Economic Recovery. Ensure that New York City remains a global hub of creativity, inclusion, innovation, and employment by creating public spaces proven to stimulate spending, attract and retain residents and jobs, and encourage tourism.

- Reduce the Public Health Burden on Communities of Color. Lower rates of asthma, heart disease, depression, preterm birth, autism, and other public health challenges that increase with vehicular pollution, decrease with access to open space, and disproportionately affect Black and Latino communities.

- Fight Climate Change. Meet our city’s climate goals by targeting cars and trucks, the city’s second-largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions.

- Save Lives. Prevent pain and suffering for the hundreds of New Yorkers killed in traffic crashes every year, the tens of thousands injured, and their families.

- Increase Quality of Life and Life Expectancy. Improve lives by raising air and water quality, reducing noise pollution, encouraging social and physical activity, increasing accessibility, and creating new public space to plant trees, add benches, and make space for children to play.

Source: Kohn Pedersen Fox / Urban Design Forum

Source: Kohn Pedersen Fox / Urban Design Forum

- Improve Fiscal Health. Solve the double parking problem by adding space for clean and electric freight and for-hire vehicles, and derive new, sustainable revenue for New York City by fairly pricing the curb and dramatically expanding metered parking.

- Create Space for People. Transform crowded sidewalks hemmed in by curbside trash mounds into broad boulevards for walking and shopping, making every street passable for strollers and wheelchairs, with space for benches, street vendors, bus shelters, bike parking, and public restrooms.

- Lower Costs. Drastically reduce the $6 billion dollar burden that traffic crashes and congestion leave on New York City’s economy every year.

- Make Streets Accessible. Make our streets safer and more inclusive for New Yorkers with vision, mobility, and hearing impairments by improving safety and visibility at intersections with curb extensions, curb cuts, accessible pedestrian signals, widened sidewalks and a network of Open Streets, and by rebuilding impassable and often hazardous existing sidewalks.

- Reduce Gridlock. Improve road conditions and reduce congestion for those who need to drive by providing alternative transportation choices, and pricing congestion, commuting, and the curb appropriately.

Once we make the decision that public space should be prioritized by its best possible public use, the only logical next step is to reduce space for cars and increase space for people. A protected car-free bus lane can move more people with greater efficiency than a hundred cars ever could. A protected bike lane can provide more value to the economy, our health, and the environment than multiple lanes of traffic. Even a tiny bit of greenspace or a pair of benches is enough to clean the air or start a conversation, each a step to a higher quality of life for all New Yorkers.

Source: Etienne Frossard

Source: Etienne Frossard

These changes are also good politics. New York City voters overwhelmingly support all of these ideas — bus lanes, bike lanes, bike share, safer crosswalks, benches, parklets, playgrounds, and Open Streets — even when building them requires the loss of parking.

BUILDING ON RECENT SUCCESSES

When the Covid-19 pandemic overtook New York, the City closed many streets to cars to make space for safe physical distancing and the reopening of small businesses. The lesson learned was that the status quo — public space long dominated by car traffic — was not the only way that streets could be. The rapid creation of Open Streets and outdoor dining showed that converting car-filled streets to better use can be done quickly and inexpensively and can deliver huge benefits to essential workers, small businesses, children, older adults, people with disabilities, low-income communities, communities of color, and central business districts.

These were not new ideas for New York City. From the pedestrianization of Times Square to the launch of the city’s first car-free busway on 14th Street, New York City knows how to reimagine streets. Each of these ideas was an individual success in terms of transportation efficiency, public safety, public health, and the local economy — proof that converting car space into space for people works. Now, future leaders of New York City must scale these successes, and use our streets as a pathway for New York City’s recovery.

The City of New York faces a daunting budgetary crisis. Recovery will require a new look at assets that have been historically misused and underutilized — like 6,300 miles of streets and three million free parking spaces — as potential tools to support our city. There is no question that our public space is inequitably distributed. Addressing this inequity will produce economic gains and cost reductions in public health, public safety, and the environment that will easily outweigh the initial investment. With the potential for revenue generation, job creation, and dramatic long-term cost reductions in health and infrastructure spending, converting car space into space for people is an opportunity that we cannot afford to miss.

Faced with the monumental challenges of economic recovery, mounting inequality, increasing traffic violence, climate change, and the potential for more pandemics on the horizon, it is time to make a fundamental shift in what purposes our public space serves, and ensure that the New York City of the future is built for people, not cars.