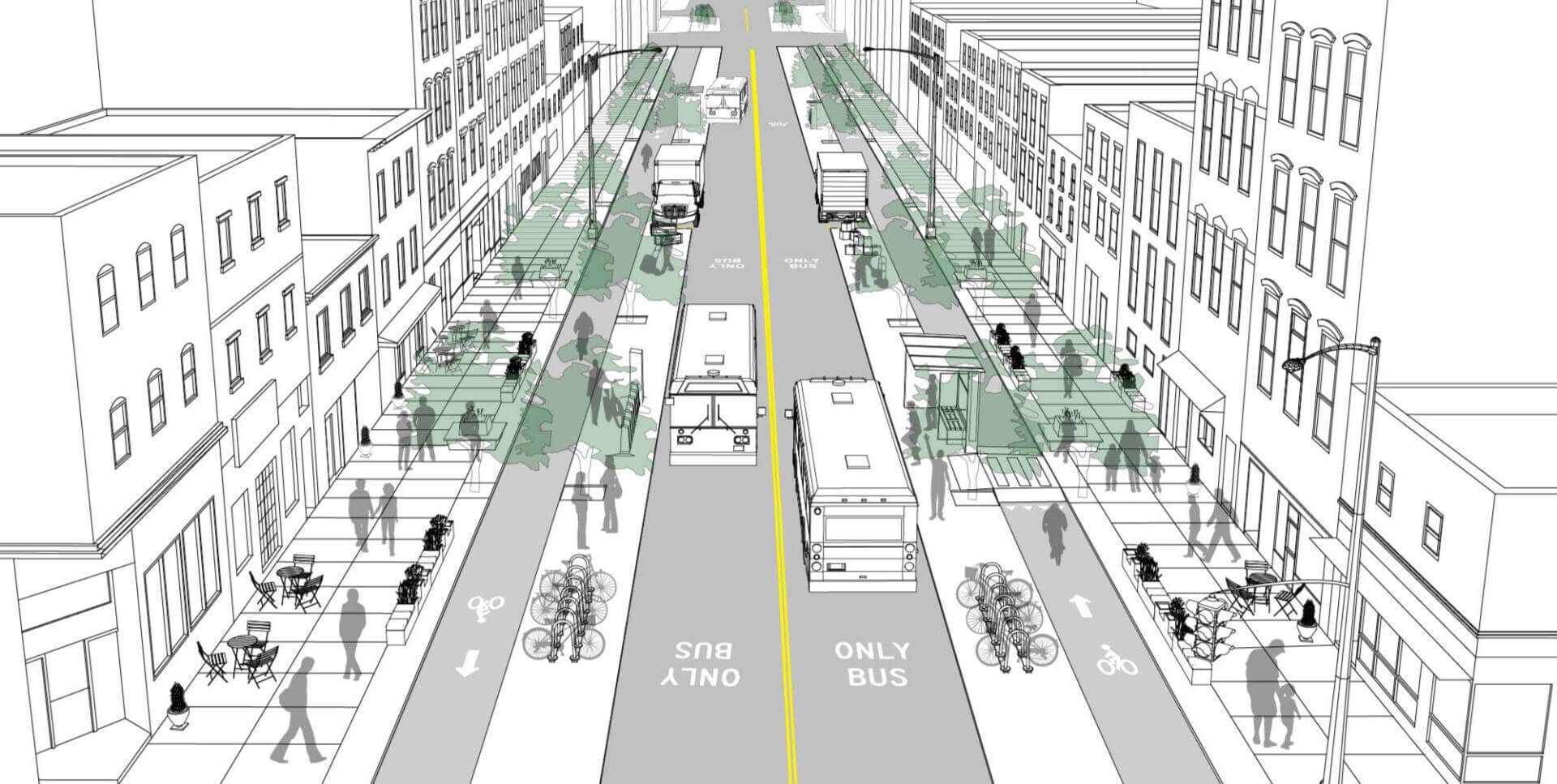

By converting car space to better use, the City of New York can boost the economy, make progress toward our climate goals, protect the safety of New Yorkers as they move about their neighborhoods, and make strides toward creating a healthier and more equitable city. Transportation Alternatives envisions a city where streets are elevated to serve as many New Yorkers as possible, with a car-free bus lane, protected bike lane, and green space within a quarter mile of every New Yorker’s home, and a wealth of new multi-use space that replaces car storage with community benefit. For the next leaders of New York City, converting car space into space for people is an opportunity backed by a wealth of evidence that converting space for cars into space for people is popular and will provide immediate economic, environmental, public health, and public safety benefits.

Source: Source: Carly Clark / Street Plans

Source: Source: Carly Clark / Street Plans

The danger and congestion caused by giving over the vast majority of public space to car traffic comes with significant public and private costs: emergency services, property damage, medical care, insurance, travel time, and time lost. At the same time, converting this car space into space for people produces significant economic gains on the citywide, community, and individual levels — and this is true for every possible non-car use of that space. Bike infrastructure benefits small businesses. Bus lanes boost transit budgets. Parks and pedestrian spaces mean more jobs, more tourism, and more money spent where it is needed most.

Transportation access enables upward mobility. Deprioritizing car traffic will allow more space for buses and better access to existing transit hubs, making public transit commutes shorter. Researchers have found that efficient transportation access plays a significant role in upward mobility, with shorter commutes helping to move people out of poverty. Today, one million New Yorkers travel more than 60 minutes each way to work. Two out of three of these commuters earn less than $35,000 per year. Non-white New Yorkers are more likely to have longer commute times, while white New Yorkers have below-average commute times.

Source: Carly Clark / Street Plans

Source: Carly Clark / Street Plans

Saving time saves money. Congested streets cost New Yorkers $1.7 billion in travel time and 87 million hours of lost time every year. Converting car driving and parking lanes in Mexico City, Mexico into a connected network of car-restricted bus lanes saved individual commuters a collective of $142 million in travel time. And similar initiatives in Johannesburg, South Africa, and Istanbul, Turkey, saved individual commuters 13 minutes per trip and 52 minutes per day, respectively.

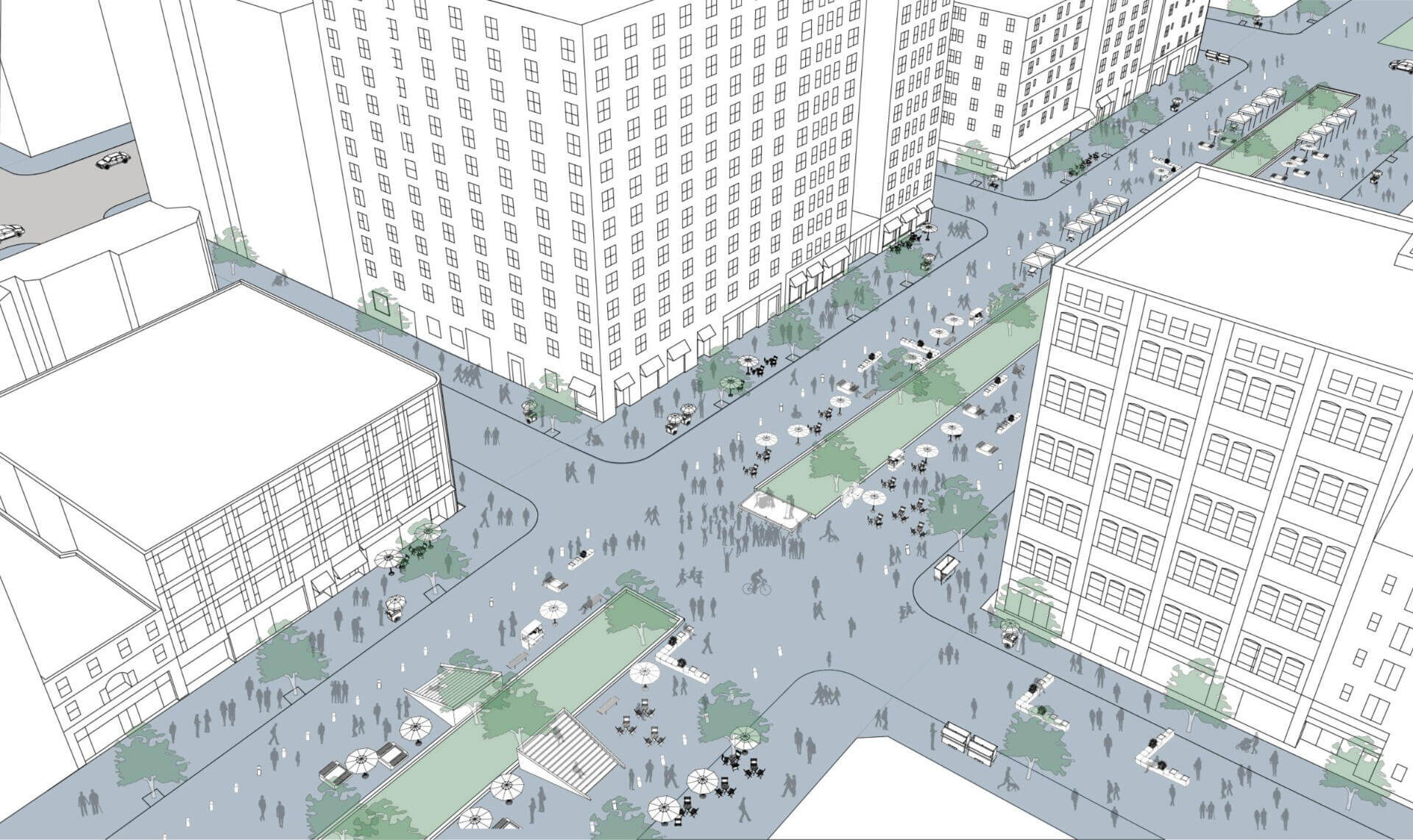

Car space converted to pedestrian space raises revenue. More walkable neighborhoods create more accessible shopping districts and benefit local economies. New York City has seen several recent examples of this effect, including a new pedestrian plaza on Pearl Street in Brooklyn that brought a 172 percent increase in sales for local businesses. Other recent examples of conversion of car parking and driving lanes into pedestrian space that have benefited local economies include Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn, Fordham Road and Pelham Parkway in the Bronx, as well as St. Nicolas and Amsterdam Avenues in Manhattan.

Car space converted to bike space raises revenue. Converting car space to bike space also benefits local economies. On Ninth Avenue in Manhattan, protected bike lanes led to a 49 percent increase in sales for local businesses. In Melbourne, Australia, converting one car parking spot into multiple bike parking spaces led to a three-and-a-half-fold increase in spending at local businesses. Researchers examining six cities that converted car parking or car travel lanes into bike lanes found that local business always saw an increase in sales. One car parking space can comfortably fit 20 bicycle parking spaces, and space used by bicycles generally generates 3.6 times more expenditure than space used by cars. In New York City, people on bicycles are much more likely to shop where there is secure bicycle parking. People on bicycles are better customers, spending significantly more money than those who drive.

Bus lanes boost transit budgets. Deprioritizing car traffic could also help save a struggling public transit system. Researchers have found that a network of car-restricted bus lanes not only increases the potential per-person capacity of traffic lanes and reduces the citywide cost of congestion and crashes, but also causes a significant number of people to shift from car travel to public transit, creating an additional pool of transit revenue. Converting car driving and storage lanes on 14th Street, Manhattan into car-restricted bus lanes brought a 17 percent increase in ridership in just two months, so much so that the City needed to purchase additional buses. In general, more walkable streets increase transit use, while guaranteed on-street parking increases the likelihood of car ownership and driving, regardless of transit access. In the last decade, Seattle spent the most per capita of large metro areas on new transit projects and accordingly saw the largest decline in the share of people driving alone to work and the largest drop in car ownership.

Streets for people boost jobs and tourism. The Trust for Public Land has found that a well-maintained, integrated network of citywide open spaces can increase tourism spending by 20 percent. A broad-scale expansion of the popular Open Restaurants program could help to shore up the close to three hundred thousand hospitality jobs that have been affected by economic uncertainty. Building bike and pedestrian infrastructure has also been found to create more jobs per million dollars spent than road infrastructure. And improving pedestrian connections across busy thoroughfares, under freeway overpasses, or through other car-dominated spaces that separate residential neighborhoods from adjacent commercial districts will benefit local businesses.

Safety has an economic value. Nationally, the status quo of unsafe car traffic is borne by individuals uninvolved in crashes, who pay nearly three-quarters of all crash costs through insurance premiums, taxes, and travel delays. In 2010 alone, dangerous streets cost New York City $4.29 billion in the cost of traffic crashes. In Bogotá, Colombia, the transformation of car lanes into a network of connected bus lanes saved the city $288 million in avoided traffic injuries and fatalities.

Source: Carly Clark / Street Plans

Source: Carly Clark / Street Plans

New York City is facing a climate emergency. Between 2017 and 2019, the city’s greenhouse gas output increased by almost four percent. Emissions from cars and trucks — the second-largest source of the city’s air pollution — have decreased by only one percent since 2005. Maximum daily summer temperatures in New York City have been rising by half a degree every decade since 1970, and the sea level has risen more than a tenth of an inch every year since 1850 — a higher rate than the global average. In New York City, climate change will have the most significant effect on neighborhoods with the lowest incomes and the highest percentages of Black and Latino residents.

Converting 25 percent of car space to better use could be the singular factor that helps New York City reach its climate goals because cars are a major source of air pollution in New York City, with one car emitting 4.6 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually. Less space for cars will mean less air pollution, a smaller carbon footprint, and more space for alternatives that are significantly less toxic to the environment. Increasing access to protected bike lanes and dedicated bus lanes will reduce the number of people who choose to drive, reducing carbon emissions, heat island effects, and cleaning the air.

Driving reductions reduce particulate matter. Converting free parking into paid parking can reduce car usage by 20 percent, and converting half of free on-street parking into bike and bus lanes, or space for walking can cut car usage by 30 percent. When New York City shut down due to Covid-19 in the Spring of 2020, the number of people driving declined by as much as 67 percent, and harmful fine particulate matter in the air fell by 23 percent. Researchers using this “natural experiment” as a model calculated that if these levels of driving reduction were sustained for five years, the result would be a citywide 34 percent improvement in levels of particulate matter, with the greatest potential for these effects in low-income communities, Black communities, and Latino communities. The car-free pedestrianization of Times Square reduced nitrogen oxide pollution by 63 percent and nitrogen dioxide pollution by 41 percent.

Green space cleans the air and water. Converting car space into green space could correct some of the negative effects of car traffic. One tree can remove the equivalent of 11,000 miles of car emissions from the atmosphere every year, and in New York City, that adds up to $5.60 in benefits for every dollar spent planting trees. Current tree cover in New York City conserves $84 million in energy. On-street rain gardens clean the air, cool the temperature, and keep stormwater runoff and street pollution out of our waterways. One bioswale can filter 89,000 gallons of rain a year, reducing combined sewer overflow that pollutes rivers with sewage.

Source: Street Plans

Source: Street Plans

More public transit leads to less carbon emissions. A reduction in car dependence must be met with an increase in transit options. Public transit consumes half the energy of private transportation and emits only five percent of the carbon dioxide per passenger-mile, and these lower consumption levels apply to operation as well as manufacturing, maintenance, infrastructure construction, and fuel production. In New York City, 96 percent of transportation air pollution comes from cars and trucks, responsible for 29 percent of all air pollution produced in the city.

Bike infrastructure leads to greener neighborhoods. Researchers have found that promoting cycling by converting car driving and storage lanes to bicycle lanes can reduce transportation-related carbon emissions by 11 percent. Converting car parking spaces in Pittsburgh into space for bike share stations reduced demand for parking by two percent, even when controlling for lost parking space, a monthly reduction of 0.82 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions per square mile.

A city that is less dominated by cars will also have positive impacts on New Yorkers’ physical and mental health. On a systemic level, less space for cars will reduce the heat island effect and particulate matter in the air, which contribute to hospitalizations for problems like asthma. On an individual level, deprioritizing car space can save lives, especially in New York City’s poorest neighborhoods. Making sure that every New Yorker lives within a five minute walk of open space will lower rates of asthma, preterm birth, heart disease, depression, and other public health challenges, and increase the quality of life and life expectancy for every New Yorker by improving air and water quality and encouraging physical activity. Access to a citywide network of protected bike lanes within a quarter-mile of every New Yorker could make low-impact exercise more accessible and converting on-street car storage into space for on-street trash containers could reduce the stress of navigating sidewalks hemmed in by towering curbside trash piles and interactions with vermin.

Source: Transportation Alternatives

Source: Transportation Alternatives

Source: Caroline Slick / Center for Zero Waste Design

Source: Caroline Slick / Center for Zero Waste Design

Converting car space to space for people reduces pollution. Converting just one major street from car use into space for biking and walking caused nearby ultrafine particulate matter rates to fall 58 percent when New York City closed Park Avenue to car traffic for Summer Streets. (Ultrafine particulate matter is especially dangerous because it is so tiny that it can enter the bloodstream via the lungs and reach the brain and heart.) The most conservative estimates count air pollution as the cause of death for at least six percent of people who die in New York City every year. Converting car space to space for people could even make New Yorkers more resilient to the next pandemic, because higher rates of air pollution positively correlate with higher mortality risk from Covid-19.

Fewer cars leads to fewer hospital visits. Particulate matter from car traffic causes asthma, low birth weight, respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and developmental delays. In New York City, more than one in 10 children have asthma; in the Bronx, the childhood asthma rate is closer to one in five. In New York City’s poorest neighborhoods, asthma is a leading cause of emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and school absences. Researchers using the “natural experiment” of New York City’s Covid-19-related drop in car traffic as a model concluded that sustaining these levels of driving reduction for five years could result in 2,392 fewer diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder, 1,981 fewer cases of child asthma, 5,175 fewer emergency room visits and 527 fewer hospitalizations for child asthma, 944 fewer preterm births, 256 fewer term low birth weights, 7791 fewer adult mortalities, and 10 fewer infant mortalities, with the greatest potential for these effects in low-income communities, Black communities, and Latino communities.

Converting car space to green space reduces heat-related mortality. Heat-related illness and death, a growing threat in a warming climate, can also be reduced by converting car space to greenspace. In the United States, Black, Asian, and Hispanic people are 52 percent, 32 percent, and 21 percent more likely, respectively, to live in neighborhoods that are prone to the heat island effect compared with non-Hispanic whites. Researchers in New York City have found that mortality rates for older New Yorkers are significantly higher on extremely hot days, and that those elevated mortality rates track highest in low-income community districts, Black neighborhoods, and areas with the highest percentage of roadway and lowest percentage of greenspace. Urban heat island effects decline in green space and rise in areas of dense roadway, so converting car driving and storage lanes to greenspace can directly reduce urban heat island effect.

Bike infrastructure extends life expectancy. Researchers have found that when 45 miles of bike lanes were constructed in New York City, it increased the probability of any given New Yorker riding a bike by more than nine percent. The health impacts of this increase can be quantified in terms of infrastructure investment: every $1,300 spent converting car driving and parking lanes to protected bike lanes provided benefits equivalent to one additional year of life over the lifetime of all city residents. Additionally, researchers comparing the impact of Citi Bike on public health found that, between the system launch and the 2015 expansion in New York City, the resulting public health savings rose to $28.3 million. The same study showed converting car storage spaces to public bike share docks and protected bike lanes, especially in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color, could significantly prevent premature deaths and produce significant public health savings.

Open space improves mental health. In a nationwide study, researchers found that children who grew up with the least access to greenspace had a 55 percent higher risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. In Los Angeles, a study showed that residents living within a quarter-mile of a greenspace had better mental health scores than anyone living at a greater distance, and that the mental health benefits of open space access were so significant as to be equivalent to decreasing local unemployment rates by two percentage points.

Driving reductions increase friendships. Researchers have found that people who live on streets with low car traffic have three times as many friends and twice as many acquaintances as people who live on high-car-traffic streets. In New York City, people who live on high-car-traffic streets have fewer relationships with their neighbors and spend less time walking, shopping and playing with their children than people who live on low-car-traffic streets. Researchers have found that converting a residential street in a low-income neighborhood to a street that prioritizes walking and biking resulted in five times as many neighbor interactions, twice as many children playing, and twice as much time spent playing.

Fewer cars means better sleep. Sleep is a critical determinant of physical and mental health, and because car traffic is a significant contributor to noise pollution in New York City, converting car space into space for people can give New Yorkers a better night’s sleep. More than three in five New Yorkers reported that noise pollution was affecting their sleep, and more than one in three has their sleep disturbed three or more nights a week. Traffic was the most common cause of disturbances. Sleep disturbances were more common for Black and Latino New Yorkers.

Car-free space makes people happy. More public open space could engender feelings of optimism in more than nine out of 10 people who use it. Researchers in St. Louis found that 94 percent of residents who visited a car-free street felt that the change made the city more welcoming, strengthened the community, and made them feel more safe and more positive about the city.

Source: Taller KEN / Urban Design Forum

Source: Taller KEN / Urban Design Forum

New York City is facing an epidemic of traffic violence. Nearly one third of all New Yorkers have been in a traffic crash, and 70 percent of New Yorkers know someone who has been injured or killed in a crash. These numbers increase for Black New Yorkers, New Yorkers over 50 years old, New York City households that make under $50,000, and residents of Staten Island. Car crashes seriously injure or kill a New Yorker every two hours. Being struck by a car is the leading cause of injury-related death for New York City children under 14, and the second leading cause of injury-related death for seniors. Around 2,500 New Yorkers are seriously injured in traffic crashes every year. Every year, more than half of those killed are people walking and biking, and 50 percent of those who die are killed on only seven percent of streets.

There are stark disparities in the impact of this violence, with traffic crashes more likely on streets in neighborhoods with lower household incomes. Childrens’ safety is especially imperiled by streets that prioritize cars, such as the wide streets that abut New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) developments. A pedestrian or bicycle crash victim in the low-income predominantly Black neighborhood of East Harlem is more than three times more likely to be a child than in the neighboring wealthy predominately white Upper East Side. In the low-income areas of the Lower East Side and Chinatown, a person struck by a car is nearly two times more likely to be a child than a crash victim on the wealthy Upper East Side.

Changes to the streetscape that incorporate principles of universal design to prioritize use by people over cars, such as Americans with Disability Act (ADA) accessibility, universal daylighting to increase intersection visibility, and building car-free bike and bus lanes, can prevent the pain and suffering of hundreds of New Yorkers killed and the tens of thousands injured in traffic crashes every year.

Converting car space to Open Streets means fewer injuries. While there are many different types of traffic-calmed streets and Open Streets, the gold standard is an active and maintained street restricted to all but necessary local car-use, like on 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights, Queens. After New York City created the 34th Avenue Open Street and banned thru traffic by cars, injuries fell by 85 percent on this stretch of road, compared to an overall 22 percent citywide decrease in injuries during the same period of time.

Restricting car access prevents crashes. Researchers have found that fatalities and injuries are more likely to occur on streets with parking directly adjacent to crosswalks, those where drivers can make turns without restrictions, and those that have 60 feet or more devoted to car lanes. Researchers have also found that deprioritizing car movement with interventions such as daylighting, protected bike lanes, and turn restrictions have resulted in dramatic injury reductions. Fully or partially restricting car access at high-crash locations in New York City reduced injuries in people walking and biking by 41 percent and 33 percent, respectively. On residential streets, those that prioritize walking, biking, and accessibility for people with disabilities have been shown to have a 50 percent lower rate of injurious crashes than streets that prioritize driving.

Bike, bus, and pedestrian infrastructure reduces death and injury for all road users. Researchers have found that converting car storage and driving lanes into a network of connected and adjacent bike lanes increases the number of bicycle commuters, and increasing the amount of people riding bicycles in a city decreases the number of fatal and injurious crashes for people walking and biking. In New York City, converting car storage and driving lanes to car-free protected bike lanes caused bicycling ridership to skyrocket while reducing injurious crashes by 17 percent, pedestrian injuries by 22 percent, and all injuries by 20 percent. Between 2001 and 2013, when hundreds of miles of car parking was converted into bike lanes, the average risk of serious injury for cyclists fell 74 percent. Converting a car driving lane into pedestrian and bus infrastructure on First and Second avenues in Manhattan caused traffic injuries to drop 21 percent even though cycling rates rose up to 177 percent on some segments, bus ridership was up nine percent, and traffic speed and volume remained constant.