One hundred years ago, New York City streets underwent a paradigm shift. At the time, and for decades prior, city streets were open-air marketplaces and social spaces, and avenues were built for strolling and later, a place to catch an above-ground public transit line. But that all changed as the automobile became affordable to more Americans.

Cars and people briefly competed for streets. Cars won, and our city has suffered every day since. Countless small businesses were closed or relegated indoors, children were taught to stay out of the street, above-ground transit lines were dismantled, sidewalks were narrowed so streets could be widened, highways destroyed neighborhoods, car owners were saddled with crippling debt, traffic injuries and fatalities became everyday tragedies, and poor, immigrant, and Black communities bore the brunt of these changes. Car traffic took over the majority of New York City’s public space.

Today, we reap the consequences of these decisions: a struggling economy, a warming climate, a public transit system in peril, a growing car dependence causing an epidemic of traffic violence, and racial and economic inequity exacerbated by planning and transportation decisions that lock low income communities and communities of color into health crises and generational poverty.

But just as our planning and transportation decisions led us to this point, so, too, can they lead us to a better future. Solutions can be found in New York City’s largest public asset. It is time to transform our streets to a higher purpose. It’s time to give New York City back to people.

Source: Street Plans / Lyft

Source: Street Plans / Lyft

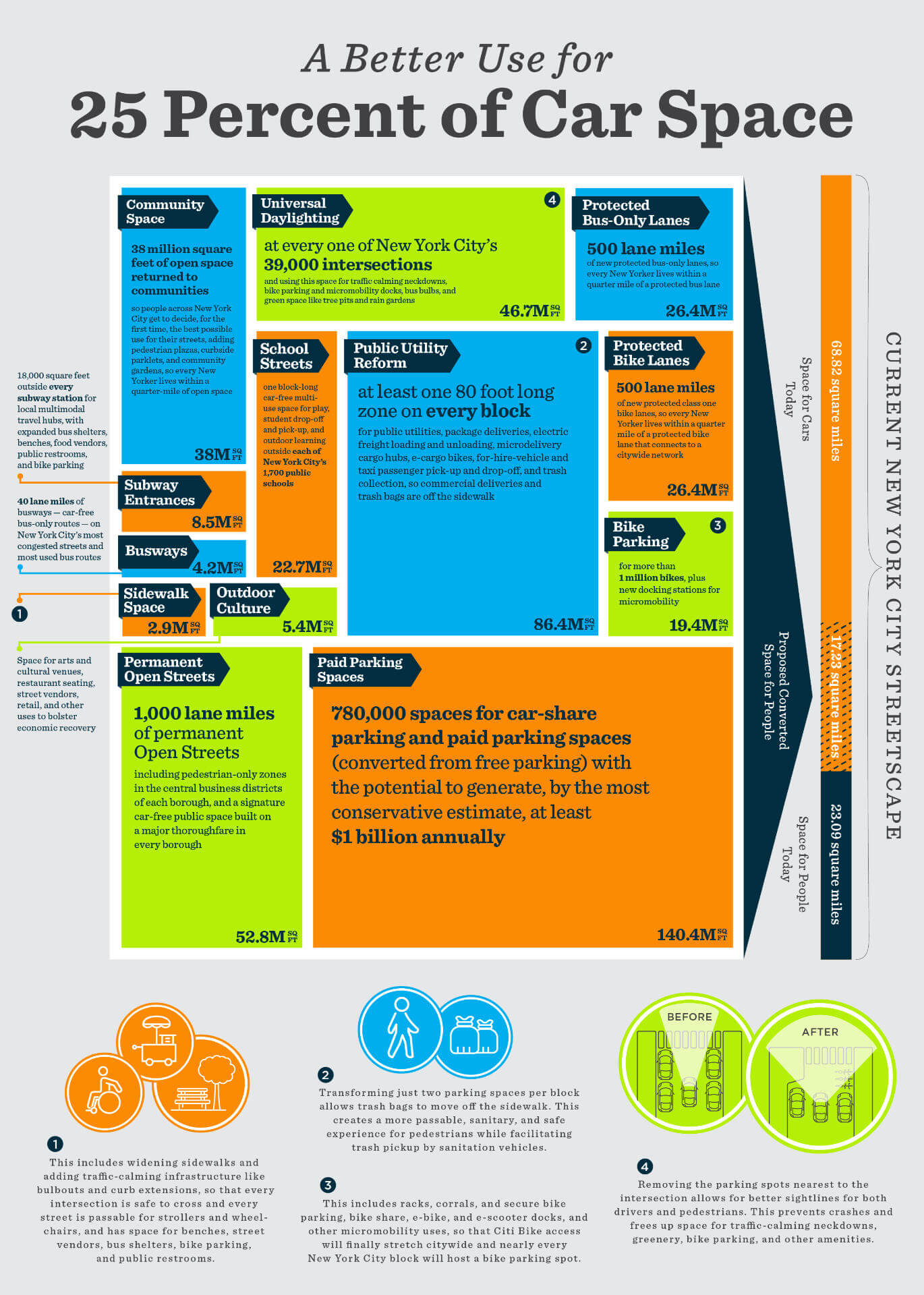

A BETTER USE OF 25 PERCENT OF CAR SPACE What could we build in place of free car parking and unending gridlock? What could we do in a city with 25 percent less space for cars and twice as much space for people? To start to imagine the answers, we need to understand just how much of our public space is given over to cars.

The best way to understand the significant amount of space New York City allocates to drivers is to hypothesize what could be built instead. Looking at converting 25 percent of the space currently devoted for cars into space for people, here is one vision of what New Yorkers could have instead:

These improvements could be located where they have the greatest possible benefit to communities and tailored to the needs of places. For example, although Lower Manhattan and Borough Park, Brooklyn, would both benefit from less car-dominated streets, the type, scale, and siting of streetscape improvements would need to match the need, opportunities, and neighborhood context of each place.

Repurposing car space for better use is not just beneficial for New Yorkers — it’s broadly popular among New York City voters in every borough, and of every age, race, and income demographic. In a recent Siena College Research Institute poll of registered New York City voters commissioned by Transportation Alternatives, every one of these amenities remained extremely popular, even if they would mean less street parking space.

A separate New York City Department of Transportation poll revealed similarly overwhelming support for street space improvements: 64 percent of residents — not just registered voters — supported reclaiming space for protected bike lanes, and only 13 percent were opposed; 66 percent supported bus lanes, and only 11 percent were opposed; 52 percent supported bike parking and 64 percent supported outdoor dining space, with only 17 percent opposed in either case.

Source: “Public Square” / FXCollaborative

Source: “Public Square” / FXCollaborative

THE QUESTION OF CONGESTION Like in a tiny New York City kitchen, in a finite city, an efficient use of space must be a priority. As New York City’s next leaders take up the challenge of a more equitable distribution of streets as public space, efficiency must be goal number one. And if an efficient use of space is the goal, the car is the worst possible choice. A single car lane on an urban street can move, at most, 1,600 people in cars an hour. Mix that car traffic with traffic from trucks and buses, and you can move, at most, 2,800 an hour. A two-way protected bike lane can move 7,500 people an hour and a sidewalk 9,000. A car-free bus lane can move 8,000 people an hour. A busway on a car-free street can move 25,000 people an hour in each direction.

Source: NACTO

Source: NACTO

Despite these known facts, little progress has been made toward spatial efficiency and congestion reduction. The per capita number of cars in New York City has barely budged since 1970. In Manhattan’s central business district, 80 percent of those who park on the street park for free and two in five drivers on the street pass through without stopping or parking. The City of New York has declared congestion levels, which are at their highest rate in decades and rising, as “unsustainable.”

All this is the result of elected officials’ failure to reduce space for cars. This is known as “induced demand” — a phenomenon where increasing the supply of something further increases the desire for it. Research beginning in the 1960s demonstrated that building roads and parking increases driving, and a recent wave of similar research has found that this effect is substantial — a one-to-one relationship where an X increase in car capacity increases driving X percent. The inverse is also true; reductions in space for cars reduces car ownership and driving. Even in transit-friendly areas of New York City, researchers found that parking creates traffic, while improvements to infrastructure for transit, walking, and biking all decrease driving.

New York City’s population is projected to swell to nine million by 2040. We cannot move buildings to make roads wider, so our only option is to rethink our spatial equation. To accommodate more New Yorkers, we need to make more efficient use of our finite public space and ensure that our planning and transportation decisions put people, not cars, first.

Congestion pricing — a plan to toll the Manhattan central business district, which New York City’s next leaders must implement immediately — will start to change this arrangement. There will be short and long term reductions in demand from drivers for roadspace and lower volumes of cars on the road network. This is a political leg-up for New York City’s next leaders looking to change the spatial arrangement of streets because it will be easier to change the function of these public spaces once fewer cars are in the way.

Clearing the way of car traffic, so New York City’s buses are a viable form of transportation, and expanding the Fair Fares program, so every New Yorker can afford the bus, should be first steps in any reimagining of New York City’s streets. Safe access for bikes, which can be an affordable lifeline for so many New Yorkers, should be a second priority, along with the citywide, City-subsidized expansion of the bike share program. These steps will clear the way of gridlock for those New Yorkers who need to drive.

Across New York City, the mistakes of the Robert Moses era — massive urban highways that induce demand for driving while delivering pollution and raceway speeds to residential neighborhoods — remain standing. These destructive highways — from the Cross-Bronx Expressway to the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway — are more often than not located in low income neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color, are not just inherently harmful, but currently crumbling, having reached their natural lifespan and now requiring a wealth of one-off repairs. A more cost effective way forward that is more in line with New York City’s climate and public health goals would be to tear down or repurpose those highways. Cities from Paris, France to Rochester, New York have begun to tear down highways to better align their streets with the goals of their city, whether those goals are addressing climate change or encouraging economic growth. It is time that New York City stops wasting money on bandaids for aging highways and starts tearing down our mistakes.

Source: Street Plans

Source: Street Plans