A wholesale reimagining of our street space could change the lives of residents across New York City. What if your neighborhood had more amenities — more benches, public restrooms, bike share, and pedestrian plazas? What if there were fewer cars inching into the crosswalk? What if the sidewalks were wider and free of trash, the protected bike lanes and bus lanes more convenient, and the open space closer than ever? What if the public street space in your neighborhood served the needs of you and your neighbors?

New York City’s next leaders have the opportunity to convert car space into space for people in a way that can change the equation for every New Yorker.

For the low-income commuter who relies on public transportation, there could be a route to economic mobility. Today, New York City’s buses are the slowest in the nation, and the New Yorkers who could most benefit from time savings, lower cost commutes, and access to more jobs are often relegated to buses trapped in car traffic. Researchers have found that efficient transportation access is the single most important factor affecting the potential to escape poverty. The median income of bus riders is substantially lower than those of subway riders or New Yorkers overall, and bus riders are less likely to have a bachelor’s degree, more likely to be a single parent, more likely to be foreign-born, more likely to be a person of color, and more likely to have a child at home. Converting car lanes into protected bus lanes on Fordham Road in the Bronx improved bus speeds by 20 percent, and the same changes to the M60 bus line in Manhattan reduced travel times by 36 percent, with no increase in congestion for private car drivers.

For the low-income immigrant worker who relies on a bike, there could be protection from the risk of premature death. In the past year, 92 percent of all cyclists were killed on streets where the median income is below the city average. The Bronx — the borough with the highest rate of poverty — is home to only six percent of all on-street protected bike lanes and only six percent of bike share docks. Converting car lanes to a citywide network of protected bike lanes (as laid out in the Regional Plan Association’s Five-Borough Bikeway) could save lives. The protected bike lane on Ninth Avenue in Manhattan reduced injury-risk to cyclists by 65 percent.

For the New Yorker with heart disease or asthma, there could be cleaner air to breathe and a faster and easier way to arrive at open space. Today, one in six New Yorkers who die from heart disease or stroke are under 65, and these deaths account for one in four premature deaths. For Black New Yorkers, the rate of premature death due to heart disease is almost twice that of white New Yorkers. One in 10 children in New York City and one in 12 adults have asthma. Air pollution from particulate matter is directly linked to heart disease and asthma, and car traffic is a leading contributor to air pollution. Converting car space into pedestrian plazas in Times Square reduced nitrogen oxide pollution by 63 percent and nitrogen dioxide pollution by 41 percent. Both pollutants lead to direct health consequences in humans, including cardiovascular and respiratory health disease.

For the frontline healthcare worker, there could be an easier commute after a long day at an essential job. Today, healthcare is the largest industry in New York City and is so large that more than a quarter of private-sector workers in the Bronx work in healthcare. These workers ride the bus more than workers in any other industry excluding social work and have the longest commutes in the private sector. A 2017 survey of members by United Healthcare Workers East ranked transit as the number two stressor among home health aides, second only to the death of a family member. The same survey found that the bus was so unreliable that some companies pay for for-hire-vehicles to transport staff. Protected bus lanes for the M34 route in Manhattan increased bus-in-motion speeds by 26 percent and decreased delays at traffic lights by 29 percent, and for the M14 route, the 14th Street car-free busway reduced travel time by 47 percent.

For the New Yorker who owns a small business, there could be a wealth of new opportunities, as wide sidewalks, and bike and bus access expand customer bases. During the Covid-19 crisis, small business revenue dropped by more than a quarter, one third of all small businesses closed permanently, and 90 percent of restaurants could not pay their rent. These small businesses represent 98 percent of New York City employers and provide jobs to three million people — roughly half the workforce. Converting car space on Eighth and Ninth avenues in Manhattan into parking-protected bike lanes and safer crosswalks brought a 49 percent increase in sales for local businesses.

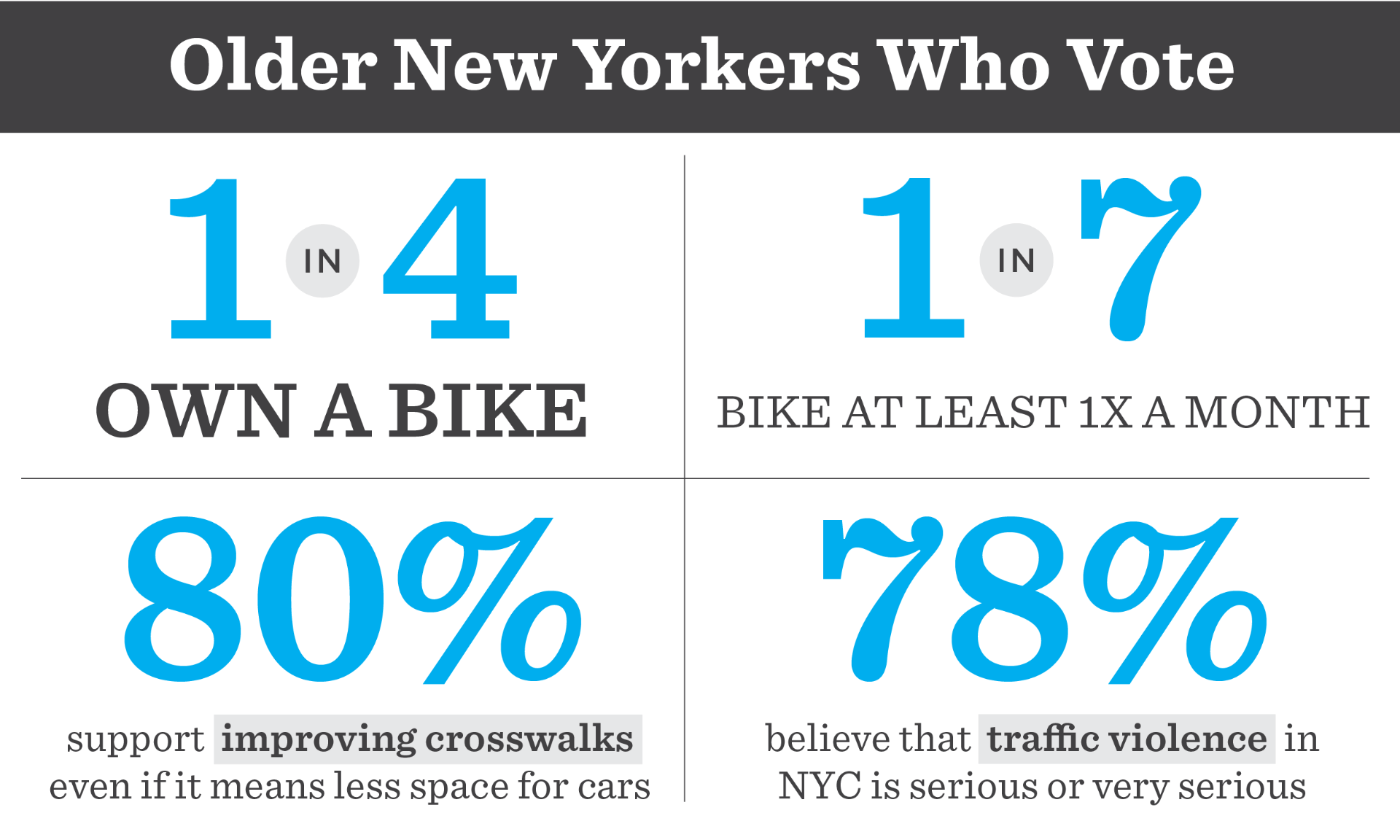

For the older New Yorker, there could be the opportunity for safe mobility that allows them to remain active and engaged in their community. Today, being struck and killed by a driver is the second leading cause of injury-related death for New Yorkers over 65, a fatality rate four times that of younger New Yorkers. New York City’s population is aging, with more than 14 percent of New Yorkers (and 22 percent of voters) now over the age of 65. This growing demographic is working longer, and biking and walking to work at an increasing rate. Buses, free from the staircases of the subway system, remain a critical form of transportation for seniors, and AARP supports converting car space into car-free Open Streets as a public health intervention for older people. An initiative to convert car space in 41 areas of New York City into daylighting, sidewalk widening, and pedestrian safety islands resulted in a 17 percent decline in senior pedestrian fatalities in these areas.

For a parent of a school-age child, there could be a safe, accessible, and nearby place to take a restless child. Today, there are only eight playgrounds for every 10,000 children in Brooklyn, the least of any borough. The few play spaces available are subpar, with 24 percent rated as being in “unacceptable” condition by the New York City Comptroller. Converting a street outside every New York City school into a playspace for our city’s more than 1.3 million students and offering up car parking for community use in every neighborhood could offer kids new safe spaces to roam and parents a reprieve outside of school and home. Three out of four school-aged children in New York City are not driven to school, and more than one in three walk. Protected bike lanes, widened sidewalks, and Open Streets would help provide safe routes to school and encourage walking and biking for teachers, students, and their parents.

For New Yorkers living with a disability that affects their mobility, there could be a more accessible city with fewer barriers to getting around. Today, more than one in 10 New Yorkers are living with a disability, and more than half of those disabilities are ambulatory. But our sidewalks are commonly blocked by obstacles, like towering piles of garbage, and more than half of neighborhoods served by the subway system do not have any accessible stations, meaning hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers with disabilities must rely on Access-A-Ride, the bus, or bikes. Converting parking spaces into drop-off and pick-up zones and storage for garbage could give Access-A-Ride vehicles, which make 6.1 million trips a year, clear access to the curb and keep sidewalks clear for easy mobility. Converting car space into bike lanes and working with Citi Bike and micromobility operators to offer models for those with ambulatory disabilities could provide safe transportation alternatives for people with disabilities. A network of car-free Open Streets could ease travel in a wheelchair without the worry of impassable sidewalks and inaccessible curbs.

For the New Yorker who currently needs to drive for work, there could be easier commutes, more available parking, and the gift of time returned. Today, New Yorkers who need to drive, such as delivery drivers, taxi drivers, or contractors who commute with heavy equipment, are wasting huge amounts of time in traffic because there are so many elective drivers on the road. Converting free car storage into demand-based, paid car parking and converting driving lanes into protected bus and bike lanes will invite elective drivers into more efficient, cheap, and pleasant modes of travel, and make more space on the road and at the curb for those who need to drive. While all industries should work toward reducing car-use and ownership in their ranks, converting car space into space for people will provide alternative transportation options which accelerate that change over time. Traffic congestion in the New York City metro-area costs the truck-based delivery industry $4.9 billion a year. Researchers project that the impact of increasing curb space available to delivery drivers with the creation of loading and unloading zones would decrease all travel times in New York City by 61 percent. With demand-based pricing, searching for parking will decrease by as much as 67 percent.

For the school-age child, there could be a chance for the very first taste of independence. Today, being struck by a car is the leading cause of injury-related death for New York City children under 14, a population that includes some 1.5 million young New Yorkers. By improving safety at intersections by converting car parking spaces into universal daylighting and protected bike lanes, and closing one street adjacent to every New York City public school to cars, we can make our streets safe for children. The conversion of car space at 124 high-risk intersections near schools in New York City into daylighting, sidewalk widening, and pedestrian safety islands, brought a 44 percent decrease in injuries for school-age children at those intersections, along with an 11 percent increase in students walking or biking to school.

For the first responder, there could be fewer delays between a call to 911 and saving a life. New York City’s 911 operators field more than 4,000 calls a day. Converting car driving lanes into car-free bus lanes can provide an express traffic-free lane that first responders can rely on, speeding response times to those calls. At the height of New York City’s bike lane building boom, emergency response times were quicker than ever. The New York City Fire Department has said that bike racks do not impede their work and that bike lanes do not increase their response time. Instead, the Fire Department explicitly cited the increase in car traffic on city streets as the major factor increasing response times and noted that when there is less traffic, response times drop. In London, an Open Streets program had no negative effect on response time for emergency services, and in some locations, emergency response times improved.

Source: Kohn Pedersen Fox / Urban Design Forum

Source: Kohn Pedersen Fox / Urban Design Forum